By Tom House, PhD, with Lindsay Berra

Parents can be the biggest advantage youth athletes can have. But, they can also be their biggest disadvantage. Putting undue pressure on your son or daughter to perform to a certain level when they’re not physically developed enough to make real progress and should simply be out on the field having fun is one of the reasons why 70% of kids in this country quit sports by age 13. You want your kids to experience the power of play. It teaches them affiliation, affirmation, how to deal with adversity, to value process over outcome, to fail without repercussion and to learn from those mistakes. If they’re having fun, it’s play. But if they’re killing themselves mentally and emotionally, and if it hurts more to lose than it feels good to win, it’s not fun and it’s not play. As parents of youth athletes, we have to realize that the way we interact with our child athletes, and their coaches and umpires, has an incredible impact on our kids, and that unrealistic expectations, excessive judgment and bad behavior can drive our kids away from sports, and deprive them of all that sports have to offer.

Parents Have Enormous Influence Over Their Children

It seems obvious, but parents don’t actually realize the impact they have on their kids. Research shows your son or daughter will hear mom’s voice through a tornado or a bomb, and a jam-packed ballpark is no exception. You see it in pro baseball all the time. Athletes will seek out mom and dad wherever they are in the stadium, and will hear them no matter what.

In September of 1972, I was pitching for the Atlanta Braves in Dodger Stadium, facing the left-handed center fielder Willie Davis in the bottom of the 9th inning. There was a lull in the crowd, and my mom, who had a nervous habit of clearing her throat, gave a little cough and cleared her throat. She was way out in center field, with 50,000 other people in the stands, and I heard it. I had to step off the mound and collect myself. Of course, it’s normal for parents to get nervous during tight spots or upset if things don’t go their kids’ way, but they really need to try to not make any noise until after play is complete, and when they do, they have to fight to at least be neutral, preferably be positive, and never, never, be negative. I did, however, get Willie to fly out to left field for the last out of the game.

Let the Athlete Initiate Conversation

On the way to and from the ballpark, let your son or daughter lead the conversation. Don’t overload them with performance anxiety, or have them think about anything other than having a good time. After the game, there should be no judgment of outcome. Don’t ask them, “Did you really try?” or “Why didn’t you do this?” Let the conversation flow from them, and if they only want to talk about pizza and ice cream, or they don’t want to talk at all, let it be. Your job as a parent of a youth athlete is to be neutral during the game and supportive before and after, not to be critical or evaluate performance.

Outcome is Irrelevant

There is so much research on this. In interviews with thousands of Little Leaguers, an hour after the game, they can’t remember the score or how they did, but they can tell you if they had a good time. That should be the key for parents of youth athletes though the whole process of youth sports. Outcome really doesn’t matter until you hit junior or senior year of high school when outcomes can help with college, or college when they can help with a pro contract. Parents, out of good intent, always care more about outcomes than kids do, and some of it is projection. They see their 10 year old swing or throw well, and they see Clayton Kershaw or Mike Trout when in reality it is way too soon to make any of those projections, and doing so can actually be detrimental to your kid. Parents hurt when they see their kids fail on the field, but my mom used to say, if it didn’t kill you, it builds character. We need to get back to that.

Winning and trophies really couldn’t matter less in youth sports.

The desire to win is universal. So make the best environments, memories and foundation possible for your kids. Those are the things that will last and compound forever. https://t.co/bZdE4Unvkd

— Tom House 〽️ (@tomhouse) December 23, 2021

Bring it Back to the Process

If a kid gives up a home run or strikes out, they’ll feel like they’ve let their parents down in addition to the team. They may not want to talk about it after the game, but you’d be surprised about how forthright kids can be about their emotions if you don’t paint them into a corner. Mark my words, the kid will bring it up before bedtime comes around. And when he or she does, don’t say, “Oh yeah, you really stunk it up out there.” Ask your kid, “Well, why do you think that happened?” or “What did you learn today?” And as soon as you do that, you’ve let the past go and moved back into process, so kids can learn from their mistakes instead of feeling bad about them.

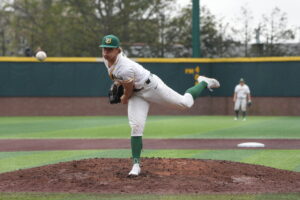

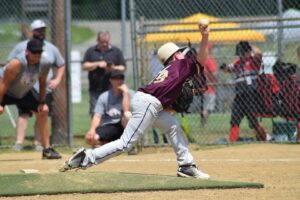

The job of a parent of a youth athlete is to be neutral or positive during the game – never negative – and supportive before and after. It is not to be critical or to evaluate performance. Photo: Crissa Thurman and daughter Stella of Glen Ridge, NJ

Parents who Coach

Coaching your own kid, whether they’re male or female, really only works up until the teenage years. Once testosterone or estrogen show up, teenage kids are designed to butt heads with their parents. At that point, the benefits of having parents of youth athletes on the field diminish exponentially, and it’s better to have third-party coaching on an individual basis, and if dad or mom has been on the field or serving as an assistant coach, it’s better to have them take a step back and let the kids play for someone who isn’t related to them. Over the last 50 years, I’ve learned that parents who are too involved can be just as detrimental as parents who aren’t involved at all. Being involved is great, but it’s better to be involved behind the scenes rather than where your involvement can be seen.

If you’re coaching your kid at a younger age, do the best you can to treat him or her like someone else’s child when you’re at the field. From a teammate standpoint, if Dad is the skipper, everything done to his particular kid is seen differently. If his kid is playing over someone else, or gets to take extra batting practice, it’s because Dad is the coach. Just hearing a kid yell “Dad!” across the field can make kids who don’t have a dad on the field uncomfortable. I remember when Reese Ryan was pitching for Texas Christian University, Nolan Ryan was an assistant coach. The head coach sent Nolan out to the mound to talk to Reese, and before Nolan got all the way out there, Reese said, “Dad, you don’t have to come talk to me, I know what you’re going to say.” The whole stadium heard it and laughed. And in that situation, it was actually awkward for the coach’s kid. So it goes both ways.

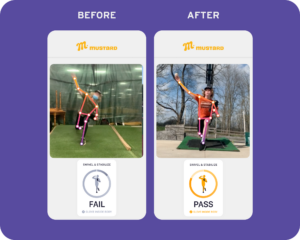

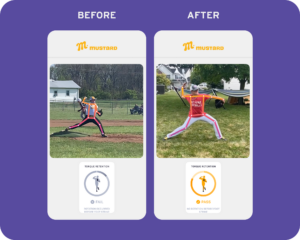

If you’d like more great content from Mustard, and you’d like to evaluate and improve your own pitching mechanics, download the Mustard pitching app today.