By Tom House, PhD, with Lindsay Berra

I’m asked all the time about how pitchers of all ages should train in the offseason, but I get two questions most often: For how long should pitchers rest their arms following the season? And is it better to stop throwing immediately or gradually decrease to a stop? Well, the answer is you should do absolutely none of that.

Think about it. Two million years ago, if hunters who threw rocks at rabbits to eat stopped throwing for a month, they’d get pretty hungry. The physical act of throwing is an adaptation and an accommodation and is not something you should start and stop. Once you start throwing, you keep throwing as long as you’re going to be a throwing athlete.

The key is managing the macrocycle and the microcycle. The big picture of your life as a pitcher is the macrocycle: In-season, offseason, preseason, repeat. And inside each of those elements is a microcycle: Prepare, compete, recover, repeat. The only difference between in-season and offseason is your level of intensity and where you focus that intensity. During the season, your intensity is centered around being competitive with the baseball. In the offseason, your intensity is focused on preparation, the building of functional strength and endurance and refilling the tank from the wear-and-tear of the season.

You throw year-round, but you don’t pitch year round. In the offseason, you never stop throwing. Of course, you do have to take a break from pitching. The mound is the only unnatural thing about pitching, and it makes pitching different from throwing. So, depending on how much you were used during the season, you should take four to six weeks away from throwing off a mound. The offseason is active rest from the mound, but everything else goes on: Strength training, mechanical drills, the throwing motion with a towel, everything you do in-season but with more intensity around building for preseason.

Our research shows weight training without some throwing is not good for a shoulder or an arm. A lot of orthopedics and doctors recommend doing nothing for a month to two months after the last game of the season, then gradually getting back into throwing. And while you’re not throwing, they recommend weight training. However, this doesn’t bring the results you’re after. New York Mets pitcher Noah Syndergaard is the perfect example. Prior to the 2017 season, he gained 20 pounds of muscle training with heavy weights with no throwing, and spent much of the 2017 on the disabled list. Since then, he has totally revamped his offseason regimen. There is nothing wrong with lifting in the offseason, but not throwing on top of it is a dead end. We suggest functional strength training to tolerance along with flat-ground throwing of any implement. You don’t have to throw a baseball, but throw something: a baseball, a softball, a football, weighted balls, or even just do the throwing motion with a towel.

Warming up is essential, whether it’s for throwing or functional training. The first four blocks of the National Pitching Association’s training program, designed to elevate the core temperature, care for the arm, and maintain flexibility and nerve patterns, can be used as a warmup for any activity. Just pick one or two exercises from each block for a proper warmup.

Block 1: Core Temperature Elevation Try jogging or skipping, forwards and backwards, carioca with the arms in the Flex-T position, anything to generate some heat. You must warm up your body to loosen up for your activity. You do not throw to warm up. Throwing to get loose is harder on a kid’s arm than over-throwing in a game situation.

Block 2: Arm Care and Recovery This block focuses on your pre- or post- throw routine to manage lactic acid, improve circulation and blood flow and care for the shoulder joint. It can include exercises like Flex-T walks, walking arm circles and speed drills with a towel.

Block 3: Upper Body Flexibility/Body Work These are your press, pull and push exercises, designed to encourage flexibility with stability. They are isometric, meaning the muscle contracts without movement of the joint, and they prepare both the acceleration and deceleration muscle groups for more work.

Block 4: Nerve Pathway Patterning This block includes throwing mechanics drills like the torque toss and rocker leaper for proper biomechanical sequencing, joint care, arm strength and speed.

Learn more about proper arm care and warm up drills. Both are especially important during the off-season to reduce injuries and maximize preparation for next season.https://t.co/buHqeBVTIo pic.twitter.com/fbzeNXod9e

— National Pitching Association | Tom House Sports (@NPA_Pitching) November 10, 2020

Volume = Load + Frequency + Intensity + Duration. If you’re building in the offseason, the intensity and the frequency should obviously be focused way more on the training side than on the competitive throwing side. But you have to be smart. Don’t over-train in the offseason and put yourself into a deficit where you will get hurt lifting heavy weights. You have to lift to your level of tolerance, not to the level of tolerance of the guy next to you, or to the specifications of some random weight training program you found on the internet.

Common sense rules apply when you are assessing training volume. If you have a 12-year-old who plays ice hockey at 5 AM, then goes to basketball practice after school and also takes piano lessons, there is a point where all the activity becomes too much. He’s going to burn out. If a young athlete is participating in a team sport, he does what the team requires him to do and that’s his full-body functional training. But around that, he takes care of what he personally needs to do. We don’t want anyone to specialize, but if he’s a pitcher, he has to go through some towel drills in the basement or play catch a few times a week to maintain the preparation and health of his arm.

You should train like you compete. A lot of people will lift upper body one day, then lower body the next. However, my philosophy is that an athlete should train his total body every time he works out. During the season, you don’t use your legs one day and then your arms the next, and your training should be representative of that. You train for function. We are not bodybuilding or strength training just to see how much we can lift. We are strength training for function, and our function is throwing a baseball. The same rules apply in the weight room that apply on the field, including that you have to work the back side of the body one-third more than the front, so when you get back on the mound, your decelerator muscles are prepared to absorb and withstand the extra force. Remember, in the offseason, you won’t be in a deficit from pitching off the mound, so your focus should be on whole-body care rather than just arm-care. And when you push the whole body, recovery is huge.

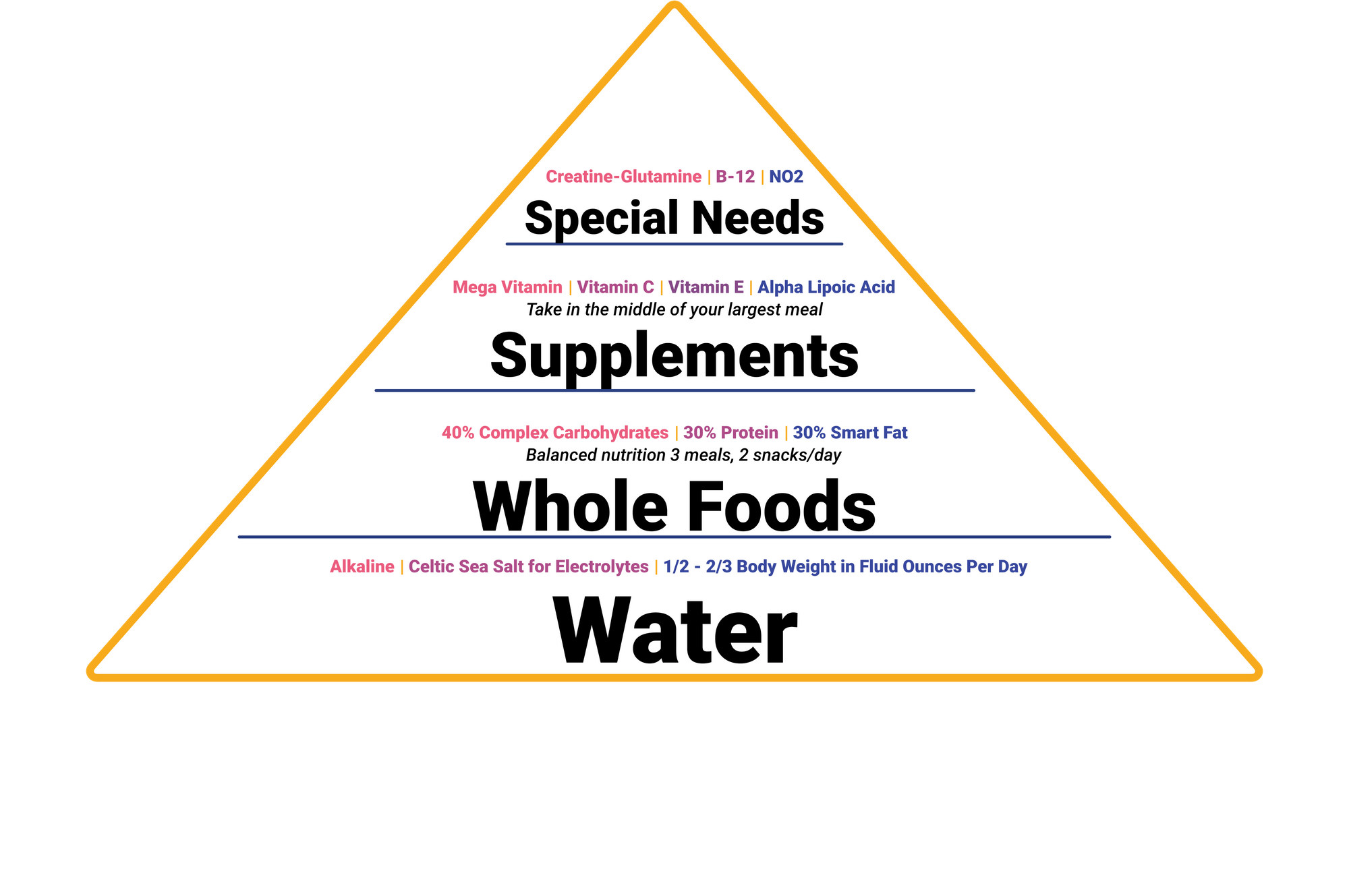

Recovery is about hydration, nutrition and sleep. In the nutrition triangle, water is at the bottom. Hydration is so important. You should be drinking one-half to two-thirds of your body weight in ounces of water per day. So, if you weigh 200 pounds, that’s 100 to 130 ounces. Hydrate early and hydrate often. If you’re thirsty on the bench or during a workout, you’re not going to catch up during that game or session. Next, unless there are specific dietary restrictions, young athletes should eat a balanced diet with a 40-30-30 percentage split of carbohydrates, protein and smart fats. It’s the best place to start so they can learn what works best for their bodies. Additionally, supplements like a multivitamin, vitamin C for adrenaline production, vitamin E for circulation and alpha lipoic acid for nerve function are a good idea. Lastly, you need to get the proper amount of sleep, and sleep cool and dark. The most important sleep time is the four hours right after you fall asleep, when your deep sleep ensures physical recovery. Everything after – your REM sleep – is for neuroplasticity, when everything you learned physically and intellectually during the day gets put on the shelves. And because you don’t want to wake up during a REM cycle, set your alarm for 6, 7.5, 9 or 10 hours after you go to bed.

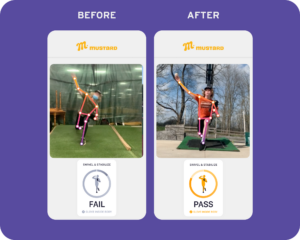

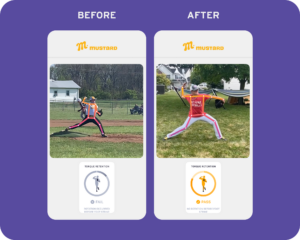

If you’d like more great content from Mustard, and you’d like to evaluate and improve your own pitching mechanics, download the Mustard pitching app today.