By Tom House, PhD, with Lindsay Berra

It’s amazing to me, that with all the science we now have on physical preparation, that there are still elite athletes who are not functionally strong. Mustard’s goal is to improve functional strength at every level of pitching by giving you a year-round training solution to build strength, improve performance and prevent injury. But, even though there is one set of rules, there are a million pitchers in the world who can interpret those rules in a million different ways. You have to discover what works best for your body, because every body is different.

What is Functional Strength?

Training for functional strength focuses on developing strength in movement patterns we use every day. For pitchers, that means developing strength that will support you through your throwing motion. This has to be done with intention, because if you just get into the weight room and start lifting weights to make a particular muscle group bigger, and you don’t also focus on the complimentary muscle groups, you can get into trouble. For throwing athletes, functional strength is the ability to accelerate and decelerate various muscles in your body with parity. You’re only as strong as your weakest link, and you’re only as efficient as your worst movement. You also can only accelerate what you can decelerate.

If a kid is playing summer baseball, but also getting ready for fall football, that individual might be in the weight room training to be ready for football. But, that doesn’t necessarily mean that program works in a baseball uniform on a baseball field. It requires a little common sense, but I would actually rather see an athlete be functionally weak than dysfunctionally strong. In today’s world, a lot of people focus on biceps, triceps, and pecs; the “beach muscles,” because teenagers love to see their biceps in the mirror. Those muscles have a lot more impact on what an athlete looks like than the teres major, teres minor and spinatus group, but the latter have more of an impact on a thrower’s health and performance.

Just another @NPA_Pitching body weight workout, the safest way to build functional strength. Great clinic this past weekend @APECDFW! Thanks to all NPA coaches who assisted. Next clinic is in Houston July 23-25, @tomhouse will be there, will you? pic.twitter.com/ttwYi03Ywa

— Dean Doxakis (@DeanDoxakisNPA) June 29, 2021

Absolute Strength v. Functional Strength

We’ve seen many players at the big-league level come back after the offseason totally ripped. That is an increase in absolute strength, which is simply the ability to move pounds. For a rotational athlete, developing functional strength means you have to sequence your movements and have a relationship between your accelerator and decelerator muscles, in both linear and angular planes.

Assessing Functional Strength

Most parents are not medical professionals or physical therapists, but there are ways they can assess the functional strength of their young athletes. There are three basic tests we do on the shoulders and one we do on the upper arms.

Subscapular Density: Look at your athletes back, and if you can get your fingers underneath the shoulder blades, one inch or to the first knuckle joint, then the subscapular density of that muscle underneath the shoulder blade is not what it should be for a baseball athlete. You need to have enough muscle underneath your scapulae to slow the arm down during swinging or throwing.

Scapular Pinch: Have the athlete raise his or her arms overhead in Flex-T or goalpost position, with elbows slightly in front of shoulder. Can he or she, without moving the arms, pinch the shoulder blades together? In Japan, if you can’t pinch a chopstick between your shoulder blades for five minutes without dropping it, you can’t be a pitcher. You can also just see if the athlete is able to pinch the side of your hand without moving the arms.

Scapular Winging & Scapular Parity: Press the palms together behind the back. That’s the first part of the test; if the athlete can’t do it, there are flexibility issues. If they cannot press the palms together, put something between the hands and press on that, and see what happens to the shoulder blade. If you have adequate strength and flexibility, the shoulders will be stable. If not, the shoulder blades will flare out. Notice whether the throwing-side shoulder blade flares more than the non-throwing side, and are there divots or dents above them. The divot is an indicator of shoulder instability, and you want to fill that up.

Biceps/Triceps: The volume of the biceps and the volume of triceps should be exactly the same. If triceps volume is smaller than biceps volume, that youngster will probably end up with an elbow issue. Muscle size needs to be equal. It’s a simple little test, and it’s not medical, but it is very common-sensical and it’s something any parent or coach or even another athlete can see.

Functional Strength Exercises to Fill The Divot pic.twitter.com/Ch5lwnRX2R

— Tom House 〽️ (@tomhouse) June 27, 2020

Should Younger Kids Strength Train?

In a word, yes. But if testosterone or estrogen haven’t yet showed up, it doesn’t do a youngster any good to try to lift heavy weight. Heavy weight is only a bonus to a strength trainer when hormones have kicked in and he or she is capable of building muscle. A pre-adolescent can do bodywork like push-ups, sit-ups, pull ups and air squats by the ton to build functional strength, but putting heavier weights on a bench or squat is just not good or necessary for 10-year-olds. They shouldn’t be training with anything heavier than the implement they use to compete. This is a good way to make sure the stuff you do to build strength doesn’t tear you down too much physically and put you in a situation where you can hurt yourself.

Should Post-Adolescent Pitchers Lift Heavy Weights?

Pitchers can certainly lift weights to build strength, but a good rule of thumb is that if you’re moving around more than your body weight, you’re probably moving around too much. That is, if you weigh 200 pounds, there’s no need to squat more than 200 pounds. If you’re a catcher, or an everyday infielder or outfielder, you can lift heavier than your bodyweight, in the right way, with proper form. I know there are many pro pitchers who like to lift heavy during the offseason, and that can certainly work for those very gifted athletes. But we haven’t found a real reason for the average pitcher to lift more than bodyweight. The risks just outweigh the rewards.

Be Mindful of Growth Spurts

Teenagers need to be aware that their bodies are going through crazy changes. If a 14-year-old freshman boy grows four inches during the summer, from a functional strength perspective, he’s not 14 anymore. He’s closer to 13, and will be until his body has time to adjust and get nerves talking to muscle again. If a junior in high school gets into a weight training program and gains 20 pounds, from a functional strength perspective, he’s not a 17-year-old anymore. He’s back to being a 16-year-old. Because every one inch of growth and every five pounds of weight gain pushes you back two months.

Weighted ball holds. Work on deceleration, strengthen the back of the shoulder and put a heavy ball in your front side hand to work on keeping the front side strong and stable. pic.twitter.com/a2kIOI6SFU

— Tom House 〽️ (@tomhouse) February 26, 2022

Balancing the Accelerators and Decelerators

Pick out any muscle on the front of the upper body and that muscle will have a reciprocal muscle somewhere on the decelerator side – or the backside – of the body. For example, the triceps is reciprocal to the biceps, the lats are reciprocal to the deltoids, and the traps and rhomboids are reciprocal to the pecs.

As it pertains to pitching, there are three muscle groups in the upper body that accelerate the arm, and only two muscle groups that decelerate it. So just by that logic, you have to work the backside of the body one-third more than the front side to achieve balance in the accelerators and the decelerators. In the lower body, four muscle groups accelerate the legs and three muscle groups decelerate them. So with the same logic, you have to work the backside of the legs one-fourth more than the front side of the legs to achieve balance.

Don’t Overlook the Obliques

With all the oblique injuries we’re seeing across baseball, it would be a mistake for any athlete to neglect to train these muscles on the sides of your core. If you’re a right-handed hitter, and you never work swinging left-handed, the decelerators on your right side aren’t going to be as strong as they should be and you’re more likely to pull an oblique. So right-handed hitters should also swing left-handed, with light, medium and heavy bats, to build parity in the torso, and vice versa. That will ensure that when you’re creating torque, or storing energy, both sides can handle the action.

2/ And swing lefty with heavy and light bats. You want both sides to have equal bat speed! You want to be able to accelerate and decelerate in both directions! pic.twitter.com/aft5RMwygk

— Tom House 〽️ (@tomhouse) February 17, 2022

Balancing Lifting and Pitching

You don’t want to push yourself to muscle failure in the weight room in the morning and then go out and try to throw five or six innings in a game that afternoon or evening. You have to be really smart about the building process of lifting weights and the tearing down process of pitching a baseball. If you’re an individual that knows you can recover in two days, you can lift Monday, Wednesdays and Friday and pitch Tuesday, Thursday and Saturday, with Sunday off. If you need three days to recover, you have to build that into your schedule. But the important thing is you never want to try to compete in game conditions on a day that you lifted weights to muscle failure.

If you can lift after you throw, that’s a great trick to help with recovery. If you go into a big league clubhouse after a night game, half the ballclub will be in the weight room, lifting at 11:30 or 12:00 at night. That allows them to push themselves into a further deficit, and then recover from the muscle failure from both pitching and lifting at the same time.

Training with Bodyweight Exercises

If you’re trying to increase functional strength, don’t isolate upper body on one day and lower body the next. Every time you resistance train, you should address the total body; right to left, front to back, accelerators to decelerators and rotation. I love all versions of the plank: belly up, belly down, right side, left side. Do pushups, flex-T pushups, squats, wall squats, jumping squats, lunges, jumping lunges, crunches. Run forward and backward, uphill and downhill. Anything in which you’re moving your own bodyweight. You’re much less likely to hurt yourself, and you’ll get strong.

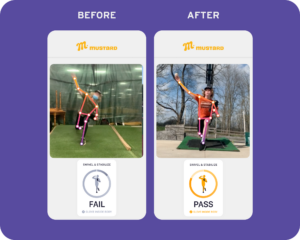

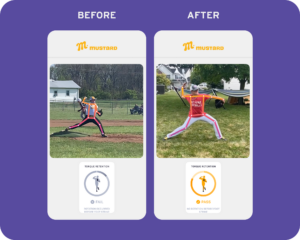

In-App Exercises for Warm-Up, Recovery and Strength Training

The exercise protocols in the Mustard app begin with core temperature elevation and address arm and joint care, flexibility, mobility, agility, strength building and recovery. With adjustments to the level of intensity, they can be used before you pitch as warm-up exercises, after you pitch for recovery and on days between throwing to build functional strength and body movement awareness.

Everything we do is cross-specific, designed to condition your body to reach maximum capacities, done with at most a light weight or resistance band. You must, however, pay attention to volume. Volume is the sum total of load, frequency, intensity and duration. You can build strength with a three ounce towel, you just have to do a million reps. You have to look at the time you have available, and where you are in your personal training plan. If you’re in rehab, you won’t do the towel drill at max intensity, or with a six-ounce ball in the towel. You’ll do everything to tolerance with volume, load, frequency, intensity and duration in mind.

If you’d like more great content from Mustard, and you’d like to evaluate and improve your own pitching mechanics, download the Mustard pitching app today.